Ugh. I knew I’d have to cover this topic at some point. Bring on the anti-politics-in-novels comments, I guess. Still, I am so excited to be featuring They Who Bring the Light by Jessica Conwell. Jessica, who I have the pleasure of knowing as Abra outside of her book covers, has written a stellar story where politics isn’t only present, but central to the entire plot. And she’s done it in a way that makes you want to keep reading. How? Hopefully, I’ll be up to the task of figuring that out.

First, come housecleaning. I will be spoiling this book, and most likely it’s predecessor, here so if that’s important to you, read it first. Always.

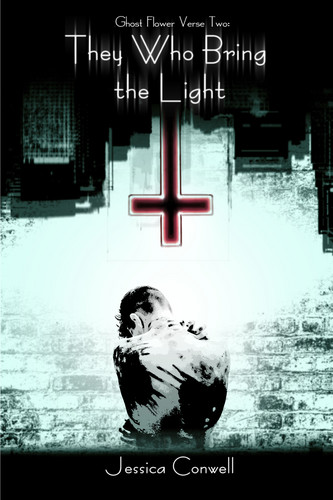

You can find They Who Bring the Light here.

Or, check out Abra’s Linktree to find more cool stuff.

Politics in fiction is one of the most contentious topics in writing today. Part of that, I think, stems from the fact that people have a hard time agreeing on what constitutes “politics”. I’ll give you my definition so that we’re all on the same page here. Politics, for the purposes of this article is: how people relate to structural power. Maybe you think this definition is overly broad. Maybe you think it describes something else. Leave those feelings at the door because this is my article and I’m talking about “politics” as broadly as possible so I can include the entire scope of definitions people use when arguing over this.

That said, I chose politics for this book, despite its many other wins, because politics is such a core part of the story. While I do believe that a writer’s politics inevitably end up in their work, this book would literally not exist if any aspect of its politics were changed. Consider the story’s timeline:

- Lyra, our newly-minted protagonist, flees Rook Lake, Ezri, their protection charge in tow.

- After seeing Ezri to safety, Lyra becomes homeless, harassed by cops for that crime alone.

- Lyra stumbles into membership with a domestic terrorist group.

- The terrorist group begins conducting an operation against an “affirming shelter” that is actually a secret conversion camp with ties to a megacorporation, with Lyra as the centerpiece.

- Lyra enters the shelter as a resident, works to become trusted by the Pastor in charge.

- Lyra shows the pastor a sample of their power, convinces him they’re an angel of the Lord, securing their place as unofficial second-in-command.

- The terrorist organization torches the shelter, and fights megacorp goons to stop the homeless queer teens who lived there from being disappeared.

Even from my simplified timeline, you can see, change the politics slightly and the whole thing falls apart. And this particular ideology soaks every page. So, how’d she do it without it feeling preachy, even to those who agree with that ideology?

The answer, I think, lies in our old friend, show don’t tell. There is never a moment in this book where exposition or dialog spell out the politics. This is aided by the fact that the story is told nonlinearly (something I could write a whole separate article about for this book). You get drip-fed the politics, not in chronological order, but very much in emotional resonance order.

It’s not: join group, find target, execute. Its more like: get to Seattle, be in this really cool shelter, but something is wrong with the pastor in charge, be homeless, see certain shelter employees be terrible, etc. It bounces back and forth, letting you build a picture yourself of this place that isn’t as kind as it seems, while at the same time telling the story of how Lyra even came to be there in the first place. If any character had just come out and said “this place is bad because XYZ so we need to do ABC”, not only would that have been grating from a political standpoint, it would have removed all mystery and emotional tension from the book. It wouldn’t be what it is.

The key to being intentional with politics is to go big. Fill it up to the brim with your politics, make the emotional core of the story dependent on them. If your politics are treated with the same seriousness you’d treat your characters or word choice, they’ll work.